- Home

- Member Resources

- Articles

- Utility of Molecular Testing in the Diagnostic Workup of Difficult-to-Classify Tumors

Histologic examination remains the core of cancer diagnosis and tumor classification. Standard diagnostic workup begins with histomorphological evaluation aided by clinical history and imaging findings and is complemented by immunohistochemistry when needed. However, some differential diagnoses cannot be resolved despite extensive efforts with conventional approaches. In the modern era, the ever-growing knowledge of the molecular mechanisms of tumor development provides additional methods toward precise classification of neoplastic diseases. Some tumor types are overwhelming represented by certain molecular alterations, for which the diagnosis can be made based on specific molecular events: eg, PML::RARA fusion in acute promyelocytic leukemia, TMPRSS2::ERG fusion in prostatic adenocarcinoma, and PAX3/7::FOXO1 fusion in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Some other molecular alterations may be seen in multiple tumor types, but in the appropriate clinical, imaging, and histomorphologic context, are helpful in classifying the tumor: eg, MDM2/CDK4 amplification in well-differentiated and dedifferentiated liposarcomas, and FET::ETS family fusions in Ewing sarcoma. However, it is much more common to encounter tumor types that lack "pathognomonic" molecular alterations. For these tumors, a more comprehensive approach in obtaining the molecular landscape may help classify the tumor when the differential diagnosis is limited. This is particularly useful with common cancer types that have been extensively studied. The genomic landscape may also help determine the clonal relationship with prior tumors, when there is a known history. Together, molecular testing has further advanced cancer diagnosis, including for those considered "cancers of unknown primary." In this article, we discuss the role of molecular testing in contemporary diagnostic workup, focusing on three challenging scenarios: 1) cancer of unknown primary; 2) difficulty in classifying a tumor with a limited differential diagnosis or known oncologic history; and 3) comparative molecular profiling to determine a clonal relationship among multiple tumors.

Scenario 1. Molecular profiling in the workup for cancer of unknown primary (CUP)

Cancer of unknown primary (CUP) encompasses a spectrum of malignancies in which the definitive tumor type and site of origin remain unknown despite extensive clinical, radiologic, and histopathologic evaluation.1-3 These cases account for approximately 3% - 5% of all cancer diagnoses and pose significant challenges in clinical management.1 In the modern era, CUP is further limited to those cases without pathognomonic molecular alterations that could otherwise point towards specific tumor types. In the past two decades, tremendous efforts, led by multi-institutional research endeavors such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) through comprehensive molecular profiling, have advanced our understanding of the genomic, transcriptomic, and even epigenetic landscapes of many common tumor types. In the challenging scenarios of CUP, molecular testing is helpful in many ways, not only to suggest a potential tumor type or primary site, but also to identify potential therapeutic targets.2

Genomic features

At a genomic level, studies have identified recurrent genomic alterations (single nucleotide variants, copy number alterations, or structural variants) as well as their frequencies in each tumor type. Studies of some tumor types were able to further classify the alterations into tumor-initiating truncal events – a common set of alterations that are present at the trunk of the cancer evolutionary tree and confer a selective growth advantage to the tumor cells, or as passenger alterations – those do not necessarily alter fitness but occurred in a cell that coincidentally or subsequently acquired a driver mutation.4,5 When faced with a CUP, identification of a typical set of truncal genomic alterations that have been described in a specific tumor type significantly increases the odds for that diagnosis. For example, a series of oncogenic/likely oncogenic mutations occurring in APC, KRAS, SMAD4, and TP53 represent the most common sequence of molecular events in colorectal cancer.6 Similarly, loss of chromosome arm 3p followed by inactivating alterations in VHL represent key early events in the development of clear cell renal cell carcinoma.7 In contrast, genomic alterations that are rare in a tumor type, or uncertain in their functional significance, usually bear less weight in suggesting the diagnosis or primary site.

Additional analyses of microsatellite instability, tumor mutation burden, and mutational signatures have also provided valuable information. Mutational signatures refer to distinct patterns of base substitutions or small insertions and deletions (indels), genome rearrangements and chromosome copy-number changes, regardless of the genes or genomic regions involved.8,9 These patterns reflect the mutational processes of exogenous and endogenous origins that may involve DNA damage or modification, DNA repair, and DNA replication.9 Some of the mutational signatures have been closely associated with an established etiology, such as the ultraviolet (UV)-induced DNA damage signature, which is characterized by a high number of C>T/G>A transitions, and the tobacco-induced mutation signature, which typically consists of a high number of C>A/G>T transversions. These mutation signatures have been found to be useful in suggesting the primary site as sun-exposed skin and tobacco smoke-exposed tissue (eg, lung and larynx), respectively.10,11 Several other mutation signatures, such as the POLE hypermutation signature (associated with loss-of-function mutations in the exonuclease domain of POLE), APOBEC-induced mutagenesis, the temozolomide-induced hypermutation signature, and the DNA mismatch repair (MMR) deficiency signature, have also been characterized in many common tumor types.9 The constellation of somatic genomic alterations, along with the mutation signatures (when predominant), could provide an even more reliable suggestion of the tumor type and primary site. For example, a poorly differentiated carcinoma with a KRAS p.G12C mutation and concurrent truncating mutations in the STK11, KEAP1, and TP53 genes, along with a prominent tobacco smoking-associated mutation signature, is most likely pulmonary adenocarcinoma.12

To better harness the genomic features for tumor classification, machine learning (ML) approaches have been utilized to develop algorithms that incorporate both discrete genomic alterations and inferred features such as mutational signatures. These algorithms are trained on a set of definitively classified tumor data to recognize these tumor types and have been shown to provide useful suggestions for tumor type or tumor origin in a significant subset of CUP cases.13,14

Transcriptomic features

In addition to the genomic alterations, the pattern of gene expression may also be unique to a specific tumor type. Studies ranging from a limited panel of genes with qPCR assays to larger gene sets with gene expression microarray or RNA sequencing have also demonstrated the feasibility of this approach.15,16,17 For quantification of gene expression, normalization and batch correction strategies are required to ensure the comparability of the data.18,19,20 In contrast, genomic features are easier to extrapolate across different testing platforms. ML or artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted algorithms have also been developed to further enhance the predictive power of gene expression-based tumor classifiers.21,22,23 Approaches that integrate genomic and transcriptomic features have also been developed.24

DNA methylation profile

DNA methylation provides a stable, cell-type-specific epigenetic signature that can assist in tumor classification. Methylation occurs primarily at CpG islands and modulates gene expression. Genome-wide methylation profiling has successfully classified CNS tumors, sarcomas, and hematologic malignancies.25,26,27,28 Algorithms such as the HiTAIC model, trained on more than 7,700 methylation profiles across 27 cancer types, identified tumor origin with 96% accuracy in a validation set of metastatic tumors.29 Another deep neural network trained on TCGA methylation data achieved high specificity and sensitivity for predicting cancer origin.30

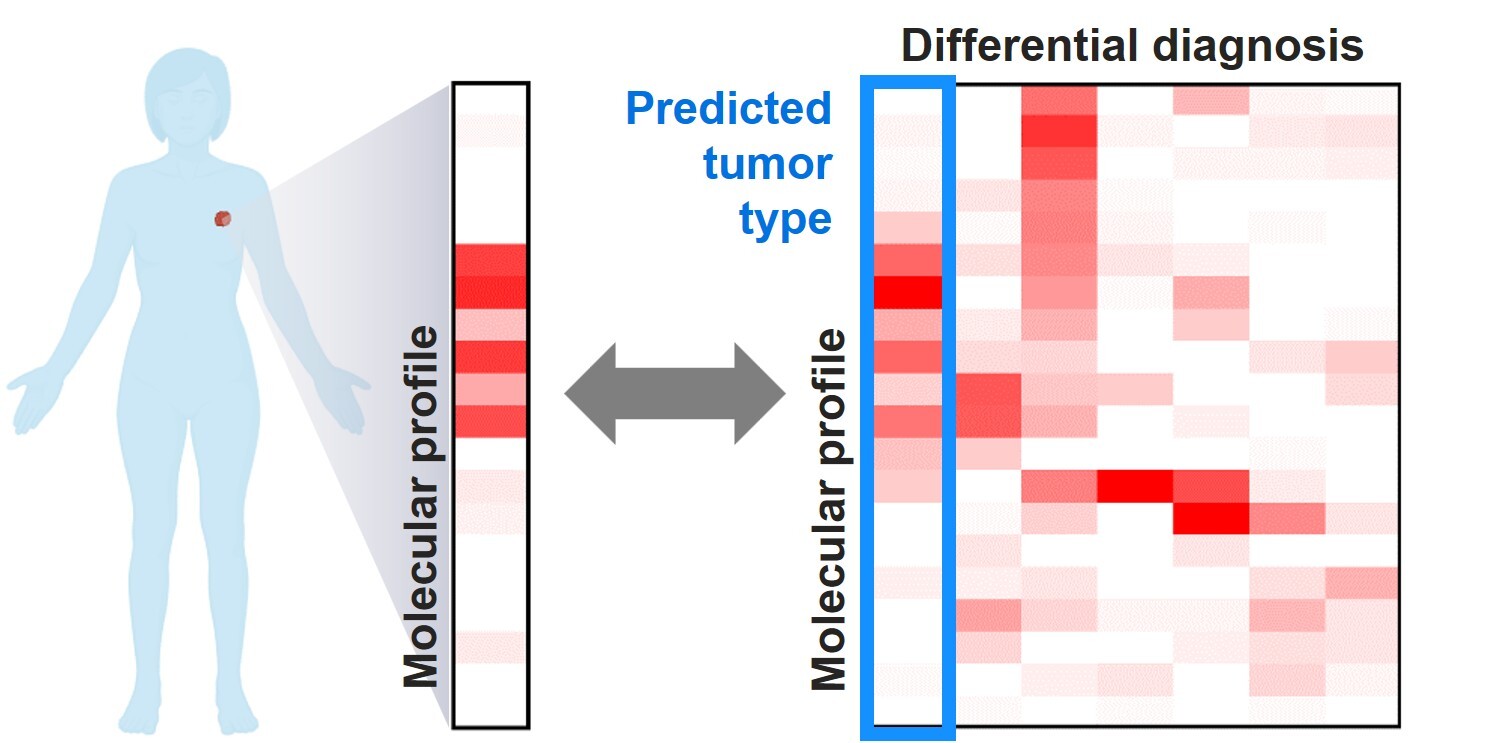

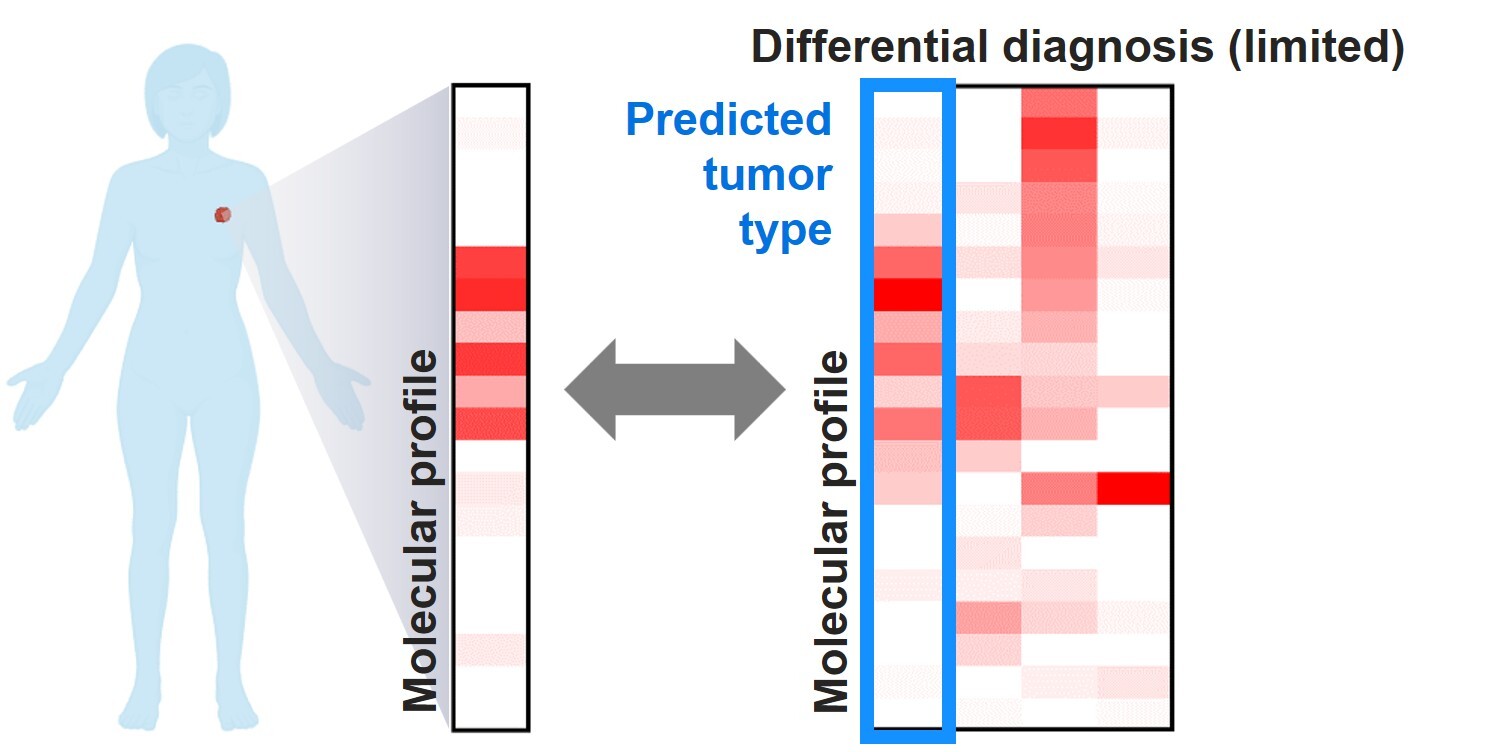

Scenario 2. Molecular profiling for difficult-to-classify tumors with limited differential diagnosis or known oncologic history

In real-world practice, it is more common to encounter tumors with challenging histomorphologic features when the patient has some oncologic history. It is also common that the location of the tumor, imaging findings, and even histology and immunophenotype of the tumor, can further narrow the differential diagnosis into a limited number of options. In this setting, the pretest probability is different from a blind prediction in CUP (Scenario 1), and tumor classification may be attempted based on the tumor type(s) or primary site(s) of highest suspicion. Some of the above-mentioned algorithms have addressed this issue by including functions to consider pertinent clinical (eg, biopsy site, primary/metastasis) and histologic findings (eg, adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma) to refine the prediction, which has demonstrated a higher accuracy than unbiased prediction.14 For other algorithms that only provide unbiased predictions, it may be confusing when the algorithm strongly favors a tumor type or primary site that is otherwise low in clinical probability. While it is plausible that the conflicting predictions from tumor type predicting algorithms may point toward a previously underexplored clinical possibility that warrants further investigation, it might be worth considering multiple top-ranking predictions from the algorithm when available.

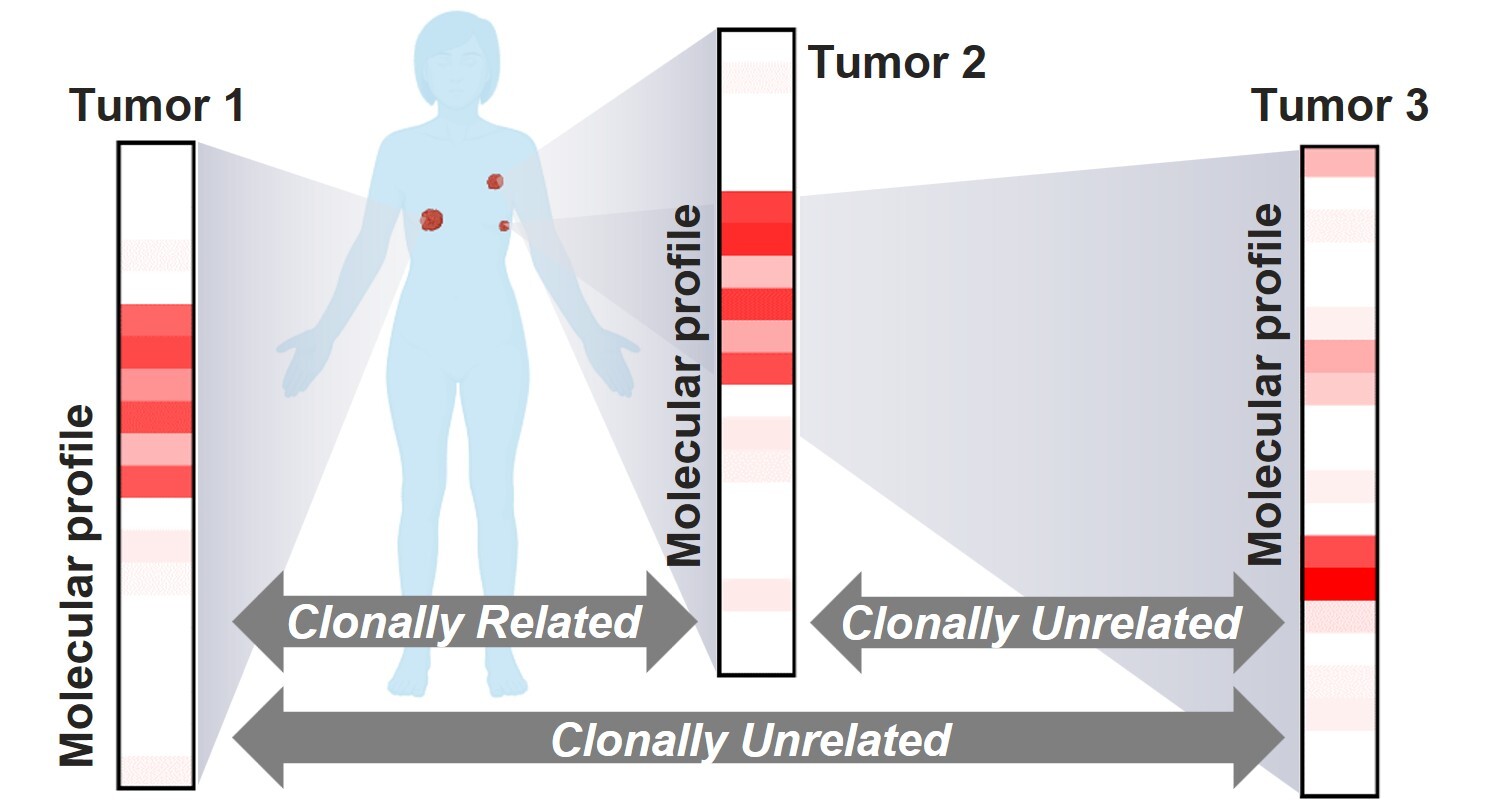

Scenario 3. Comparative molecular profiling to determine clonal relationship in multiple tumors

With the wider accessibility of genomic sequencing, patients with a new, difficult-to-classify malignancy might not only present with a known oncologic history, but also a known genomic profile from the prior diagnosis. This represents a unique clinical setting in which determination of the clonal relationship between current and prior specimens may help resolve the new diagnosis, as well as provide more accurate staging information. While many tumors have the potential to present with a recurrent/metastatic lesion that exhibits distinct histomorphologic features, this is more likely to affect tumors with higher frequencies of synchronous or metachronous tumors, such as lung, breast, and bladder cancers. Among these tumor types, this issue is best studied in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), in which distinguishing between separate primary lung carcinomas (SPLCs) and intrapulmonary metastases (IPMs) has become increasingly significant in clinical practice.

The differentiation between SPLCs and IPMs has evolved substantially since the time when the criteria solely relied on clinicopathologic findings.31 In the modern era, the use of high-throughput molecular assays such as next-generation sequencing (NGS) provides a broad assessment of genomic alterations, including both the early tumor-initiating (truncal) alterations and passenger mutations. The principle for clonal relationship assessment lies in the observation that most of the truncal alterations are preserved throughout the evolution of the tumor, and that tumors arising from a common ancestral clone share most, if not all, of the truncal mutations carried by the common clone.32 Studies in NSCLC have demonstrated that complete non-overlapping genomic profiles generated by broad-panel NGS could serve as strong evidence of distinct clonal origins (SPLCs). In contrast, multiple shared alterations support a shared clonal origin (IPMs).33,34 The caveats, however, include those tumors that share a single oncogenic driver hotspot mutation, and when the molecular testing is performed using a small panel with limited coverage.

In Western countries, NSCLCs often arise in patients with a tobacco smoking history, and KRAS p.G12C represents the most common oncogenic driver (approximately 24%). The odds for the same KRAS p.G12C mutation to occur coincidentally in two SPLCs could reach up to 1 in 17. Similarly, in Asian countries where EGFR driver mutations are common, the chances for two SPLCs to harbor an identical EGFR alteration such as p.L858R or p.E746_A750del can be as high as 1 in 12.35 In this setting, a single shared hotspot driver mutation between two tumors may be insufficient to establish a clonal relationship. SPLCs may share a single hotspot driver mutation yet show otherwise completely non-overlapping genomic profiles. In contrast to the analysis in Scenario 1 where common oncogenic driver alterations are more informative in suggesting the tumor type, alterations that occur at relatively low frequency yet are shared between two tumors would favor IPMs.33 This interpretation requires broad-panel NGS that covers sufficiently large areas of the genome. Small panels are also more likely to suffer from the lack of distinguishing power when no reportable alterations are detected, especially in the setting of driver-negative NSCLC.35

In a different tumor type, similar principles can be applied while the common driver alterations may differ. One important lesson is that the prevalence of the mutations needs to be considered when determining clonality using NGS. Despite best efforts with broad-panel NGS and careful examination by experienced molecular pathologists, there are some cases that remain inconclusive. Further studies are needed to determine whether transcriptomic or methylation profiles or integrative approaches could help address this issue.

Considerations in interpreting tumor type prediction results

It is no doubt that tumor type/primary site classifiers based on molecular features may provide valuable information in the diagnostic workup of CUP cases. More sophisticated algorithms with ML or AI-assisted approaches for informed prediction based on genomic, transcriptomic, methylation profile, and/or multi-omic features are being developed and will become more widely accessible. It is critical to note that each model or algorithm is limited by its design and validation to predict within a defined group of tumor types. In addition, due to limitations in data acquisition, most of the tumor types included in the training process of these predictive algorithms were generic categories (eg, invasive breast carcinoma), and may not reflect the most up-to-date tumor classification or cover rare subtypes that have limited data in the literature. When using these algorithms in real-world settings, it is important to consider the pre-test probabilities of the differential diagnoses and to confirm whether the diagnoses of highest suspicion are included in the training and validation of the tumor-type predictive algorithm. After all, the algorithm cannot predict tumor types for which it was not trained or validated. If the differential diagnosis includes some rare tumor types, it is also important to note the possibility that the rare tumor types may not be sufficiently represented in the training/validation datasets of the algorithm. Many of the algorithms provide a probability or confidence level for the prediction, which may be helpful to determine whether the prediction is strongly supported by the data.

In the meantime, as many studies suggest that the accuracy in tumor-type prediction increases when multiple top-ranking possibilities are considered, regard should be given to more than one tumor type. Lastly, other technical limitations in the molecular tests may also occur, such as false prediction due to low tumor purity or low-quality specimens.

Overall, it is worth noting that the results of these tumor-type prediction results should not be considered definitive answers. Rather, they should be regarded as suggestions for further investigation. The prediction is more informative when considering multiple possibilities of the highest confidence levels.

Future perspective

The rise of digital pathology has enabled the use of ML to analyze whole-slide images (WSI) for classification tasks. For CUP diagnosis, algorithms that incorporate WSIs such as TOAD (Tumor Origin Assessment via Deep Learning) have been developed to predict tissue of origin in 61% of CUP cases.36 These approaches augment pathologists’ workflow and provide orthogonal diagnostic insights complementary to molecular profiling alone.

It is also worth noting that even when the primary site and definitive tumor type remain unknown, molecular profiling may still guide treatment. Several clinical studies have suggested clinical benefit of targeted therapy based on molecular findings in CUP patients.37,38 Recent FDA approvals for cancer type-agnostic therapies provide important therapeutic opportunities for patients whose tumor remains unclassified despite best efforts, including pembrolizumab in tumors with high TMB (≥ 10 mut/Mb), larotrectinib/entrectinib/repotrectinib in solid tumors with NTRK gene rearrangements, dabrafenib plus trametinib in unresectable or metastatic solid tumors with BRAF V600E mutation, as well as selpercatinib for locally advanced or metastatic RET fusion-positive solid tumors.39-43 The approval of fam-trastuzumab deruxtecan-nxki for unresectable or metastatic HER2-positive solid tumors, relying on immunohistochemistry to evaluate the therapeutic marker, has stimulated tremendous research efforts into molecular correlates and testing approaches for HER2 and other potential targets for antibody drug-conjugates. Integration of spatial technologies may further transform the diagnostic workflow of cancer.44

Conclusions

Molecular testing has emerged as a pivotal component in the diagnostic workup of cancer, particularly in challenging scenarios like CUP, tumors with a limited differential diagnosis, and assessing clonal relationships in multiple lesions. The incorporation of genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenetic insights enables a more precise and informed classification of neoplastic diseases. Specific truncal driver events, common recurrent oncogenic alterations, and mutational signatures may help narrow down potential tumor types and sites of origin even when conventional methods fall short. The integration of ML and AI-assisted algorithms into molecular profiling further enhances prediction accuracy, allowing for a more efficient and reliable diagnostic process. In other scenarios where tumors are difficult to classify despite a known oncologic history, or when assessment of clonal relationships is needed in cases with multiple tumors, molecular testing provides valuable information refining differential diagnoses and tailoring treatment options. Although current algorithms have demonstrated substantial progress, they are inherently limited by their training datasets and may not cover rare tumor types or new classifications emerging in oncology. Hence, it is essential for pathologists and clinicians to integrate prediction results with clinical and histopathological context, continuously seeking verification and cross-validation. As the technologies and our understanding of tumor biology continue to advance, multi-omic approaches present a promising horizon for the continued refinement of cancer diagnostics and therapeutics, potentially overcoming limitations associated with single-modality techniques.

References

- Pavlidis N, Pentheroudakis G. Cancer of unknown primary site. Lancet. 2012;379(9824):1428-35. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(11)61178-1

- Rassy E, Pavlidis N. Progress in refining the clinical management of cancer of unknown primary in the molecular era. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2020;17(9):541-554. doi:10.1038/s41571-020-0359-1

- Krämer A, Bochtler T, Pauli C, et al. Cancer of unknown primary: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2023;34(3):228-246. doi:10.1016/j.annonc.2022.11.013

- Bozic I, Antal T, Ohtsuki H, et al. Accumulation of driver and passenger mutations during tumor progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(43):18545-50. doi:10.1073/pnas.1010978107

- Levine AJ, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG. The roles of initiating truncal mutations in human cancers: The order of mutations and tumor cell type matters. Cancer Cell. 2019;35(1):10-15. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2018.11.009

- Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012;487(7407):330-7. doi:10.1038/nature11252

- Mitchell TJ, Turajlic S, Rowan A, et al. Timing the landmark events in the evolution of clear cell renal cell cancer: TRACERx renal. Cell. 2018;173(3):611-623.e17. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.020

- Alexandrov LB, Stratton MR. Mutational signatures: the patterns of somatic mutations hidden in cancer genomes. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2014;24(100):52-60. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2013.11.014

- Alexandrov LB, Kim J, Haradhvala NJ, et al. The repertoire of mutational signatures in human cancer. Nature. 2020;578(7793):94-101. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-1943-3

- Kasago IS, Chatila WK, Lezcano CM, et al. Undifferentiated and dedifferentiated metastatic melanomas masquerading as soft tissue sarcomas: Mutational signature analysis and immunotherapy response. Mod Pathol. 2023;36(8):100165. doi:10.1016/j.modpat.2023.100165

- Alexandrov LB, Ju YS, Haase K, et al. Mutational signatures associated with tobacco smoking in human cancer. Science. 2016;354(6312):618-622. doi:10.1126/science.aag0299

- Arbour KC, Jordan E, Kim HR, et al. Effects of co-occurring genomic alterations on outcomes in patients with KRAS-mutant non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(2):334-340. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-17-1841

- Penson A, Camacho N, Zheng Y, et al. Development of genome-derived tumor type prediction to inform clinical cancer care. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(1):84-91. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.3985

- Darmofal M, Suman S, Atwal G, et al. Deep-learning model for tumor-type prediction using targeted clinical genomic sequencing data. Cancer Discov. 2024;14(6):1064-1081. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-23-0996

- Varadhachary GR, Talantov D, Raber MN, et al. Molecular profiling of carcinoma of unknown primary and correlation with clinical evaluation. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(27):4442-8. doi:10.1200/jco.2007.14.437l

- Greco FA, Spigel DR, Yardley DA, Erlander MG, Ma XJ, Hainsworth JD. Molecular profiling in unknown primary cancer: accuracy of tissue of origin prediction. Oncologist. 2010;15(5):500-6. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0328

- Zhao Y, Pan Z, Namburi S, et al. CUP-AI-Dx: A tool for inferring cancer tissue of origin and molecular subtype using RNA gene-expression data and artificial intelligence. EBioMedicine. 2020;61:103030. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.103030

- Leek JT, Scharpf RB, Bravo HC, et al. Tackling the widespread and critical impact of batch effects in high-throughput data. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11(10):733-9. doi:10.1038/nrg2825

- Peixoto L, Risso D, Poplawski SG, et al. How data analysis affects power, reproducibility and biological insight of RNA-seq studies in complex datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(16):7664-74. doi:10.1093/nar/gkv736

- Risso D, Ngai J, Speed TP, Dudoit S. Normalization of RNA-seq data using factor analysis of control genes or samples. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32(9):896-902. doi:10.1038/nbt.2931

- Michuda J, Breschi A, Kapilivsky J, et al. Validation of a transcriptome-based assay for classifying cancers of unknown primary origin. Mol Diagn Ther. 2023;27(4):499-511. doi:10.1007/s40291-023-00650-5

- Hong J, Hachem LD, Fehlings MG. A deep learning model to classify neoplastic state and tissue origin from transcriptomic data. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):9669. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-13665-5

- Grewal JK, Tessier-Cloutier B, Jones M, et al. Application of a neural network whole transcriptome-based pan-cancer method for diagnosis of primary and metastatic cancers. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(4):e192597. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.2597

- Abraham J, Heimberger AB, Marshall J, et al. Machine learning analysis using 77,044 genomic and transcriptomic profiles to accurately predict tumor type. Transl Oncol. 2021;14(3):101016. doi:10.1016/j.tranon.2021.101016

- Capper D, Jones DTW, Sill M, et al. DNA methylation-based classification of central nervous system tumours. Nature. 2018;555(7697):469-474. doi:10.1038/nature26000

- Sill M, Plass C, Pfister SM, Lipka DB. Molecular tumor classification using DNA methylome analysis. Hum Mol Genet. 2020;29(R2):R205-r213. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddaa147

- Koelsche C, Schrimpf D, Stichel D, et al. Sarcoma classification by DNA methylation profiling. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):498. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-20603-4

- Giacopelli B, Wang M, Cleary A, et al. DNA methylation epitypes highlight underlying developmental and disease pathways in acute myeloid leukemia. Genome Res. 2021;31(5):747-761. doi:10.1101/gr.269233.120

- Zhang Z, Lu Y, Vosoughi S, Levy JJ, Christensen BC, Salas LA. HiTAIC: hierarchical tumor artificial intelligence classifier traces tissue of origin and tumor type in primary and metastasized tumors using DNA methylation. NAR Cancer. 2023;5(2):zcad017. doi:10.1093/narcan/zcad017

- Zheng C, Xu R. Predicting cancer origins with a DNA methylation-based deep neural network model. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):e0226461. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0226461

- Martini N, Melamed MR. Multiple primary lung cancers. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1975;70(4):606-12.

- Greaves M, Maley CC. Clonal evolution in cancer. Nature. 2012;481(7381):306-13. doi:10.1038/nature10762

- Chang JC, Alex D, Bott M, et al. Comprehensive next-generation sequencing unambiguously distinguishes separate primary lung carcinomas from intrapulmonary metastases: Comparison with standard histopathologic approach. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(23):7113-7125. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-19-1700

- Jamal-Hanjani M, Wilson GA, McGranahan N, et al. Tracking the evolution of non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(22):2109-2121. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1616288

- Chang JC, Rekhtman N. Pathologic assessment and staging of multiple non-small cell lung carcinomas: A paradigm shift with the emerging role of molecular methods. Mod Pathol. 2024;37(5):100453. doi:10.1016/j.modpat.2024.100453

- Lu MY, Chen TY, Williamson DFK, et al. AI-based pathology predicts origins for cancers of unknown primary. Nature. 2021;594(7861):106-110. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03512-4

- Hayashi H, Takiguchi Y, Minami H, et al. Site-specific and targeted therapy based on molecular profiling by next-generation sequencing for cancer of unknown primary site: A nonrandomized phase 2 clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(12):1931-1938. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.4643

- Cobain EF, Wu YM, Vats P, et al. Assessment of clinical benefit of integrative genomic profiling in advanced solid tumors. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(4):525-533. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.7987

- FDA approves larotrectinib for solid tumors with NTRK gene fusions. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2025. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/fda-approves-larotrectinib-solid-tumors-ntrk-gene-fusions-0

- FDA approves entrectinib for NTRK solid tumors and ROS-1 NSCLC. U.S. Food and Drug Administrationq. 2025. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-entrectinib-ntrk-solid-tumors-and-ros-1-nsclc

- FDA grants accelerated approval to repotrectinib for adult and pediatric patients with NTRK gene fusion-positive solid tumors. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2025. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-grants-accelerated-approval-repotrectinib-adult-and-pediatric-patients-ntrk-gene-fusion-positive

- FDA grants accelerated approval to dabrafenib in combination with trametinib for unresectable or metastatic solid tumors with BRAF V600E mutation. U.S. Food and Drug Administrationq. 2025. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-grants-accelerated-approval-dabrafenib-combination-trametinib-unresectable-or-metastatic-solid

- FDA approves selpercatinib for locally advanced or metastatic RET fusion-positive solid tumors. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-selpercatinib-locally-advanced-or-metastatic-ret-fusion-positive-solid-tumors

- Gong D, Arbesfeld-Qiu JM, Perrault E, Bae JW, Hwang WL. Spatial oncology: Translating contextual biology to the clinic. Cancer Cell. 2024;42(10):1653-1675. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2024.09.001

Jie-Fu Chen, MD, FCAP, is an assistant attending pathologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC), specializing in genitourinary pathology and diagnostic molecular pathology. He completed his residency in anatomic pathology at Washington University in St Louis, followed by advanced fellowships in genitourinary pathology and molecular genetic pathology at MSKCC.

Dr. Chen's research focuses on the histologic and molecular characterization of genitourinary tumors, as well as the development of liquid biopsy assays for advanced cancers.

Jinjuan Yao, MD, PhD, FCAP, is a molecular pathologist from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) with subspecialty training in molecular pathology and hematopathology. Dr. Yao also serves as the Quality Assurance Chair of Diagnostic Molecular Pathology at MSK.

Dr. Yao is a member of AMP, CAP, and USCAP, as well as a lifetime member of Chinese American Pathologists Association (CAPA). She is also a CAP International Assigning Commissioner (China and Hong Kong).

Dr. Yao’s clinical work has focused on the large-scale, prospective genotyping of solid tumors and hematologic malignancies using a variety of NGS technologies. Her research interests include the pathogenesis of leukemias and lymphomas, genetic alterations, and therapies of solid tumors.