- Home

- Member Resources

- Articles

- Culture Club: Promoting a Culture of Safety and Quality

I recently spoke with Dr. Yael Heher, assistant professor of pathology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, who is also the director of quality assurance and improvement in pathology. We discuss her interest in quality and safety and what she has accomplished in the department.

How did you get interested in safety?

Dr. Heher:

During my training in Canada, there was a significant quality issue involving erroneous breast cancer hormone receptor testing by a major centralized provincial anatomic pathology laboratory. This issue resulted in the inappropriate treatment of thousands of women with breast cancer. This large-scale patient safety event had a direct impact on the public perception of pathology in Canada. As such, the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada implemented mandatory quality requirements in pathology residency training programs. These requirements involved both the recognition of quality in the diagnostic course and the quality of care and stewardship of the entire testing process.

About a year before I joined the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, there was an incident in which prostate biopsies were mixed up resulting in performing surgery on a patient without cancer, while the patient with cancer was left untreated. This incident was a major patient safety event. A few years later, Harvard Medical School rolled out a fellowship in quality and safety. I was fortunate enough to be elected to the inaugural class. There, I was immersed in quality principles taught by giants in the field of patient safety and was able to combine this with an MPH program at the Harvard School of Public Health.

Briefly touch upon the 2015 National Academy of Medicine report and the recognition that pathologists are crucial members of the diagnostic care team.

Dr. Heher:

The 2015 National Academy of Medicine report was third in a series of white papers on patient safety. The seminal report To Err is Human (1999), highlighted and catalyzed the patient safety movement. Many consider this the beginning point in our understanding of preventable patient harm. The second report, Crossing the Quality Chasm (2001) called for a redesign in the healthcare model. In the 2015 report Improving Diagnosis in Medicine, two pathologists were included for the first time, Dr. Michael Laposata and Dr. Michael Cohen. This report targeting pathologists and radiologists was a call to action for diagnostic error. Additionally, Drs. Laposata and Cohen published a follow-up editorial in The Archives of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine outlining the goals of the report and urging pathologists to join the patient safety movement.

What have you done in your department to promote a culture of safety?

Dr. Heher:

When I arrived at Beth Israel, fear to report risk and patient safety events still existed internally, despite the changing external environment around quality. Even if fear was not a reason, the staff took pride in addressing issues at the local level without escalating concerns. Unfortunately, this would often leave leadership without an accurate assessment of patient safety risk or any ability to change systems broadly to make them safer. Thus, we worked tirelessly to educate the staff on the front line in ways to understand risk and to report safety events, including "near misses" or “close calls.”

To implement safer systems, one must understand what makes a system unsafe. We addressed this in two ways. The first was to create a process in which front-line staff could easily report patient safety events, and we made sure we responded to their concerns in a non-punitive manner. We acknowledged the problem and made sure the staff understood that we escalated the issue to the appropriate teams. Soon after, we saw a sharp rise in staff reports on safety issues. By directly involving staff in the quality improvement process we were able to shift the culture from that of a "deny and defend" to a "good catch" mentality. Feedback was given positively to the staff, showing them the changes implemented as a result of their reports. This was a private, one-on-one slow change. The second change—being a more public investment in the culture of safety—was the implementation of a pathology morbidity and mortality (M&M) conference.

Describe the Pathology M&M conference.

Dr. Heher:

Having experienced a diagnostic error that was a near miss, I looked back on the case and thought this would be an excellent learning opportunity for others since the diagnosis was a challenge and others could make the same mistake. There would be a benefit in sharing these cases in a public forum. I thought, why is there not a similar forum for pathologists to review their errors, analogous to medical and surgical M&M rounds? I had the idea to translate this M&M model to pathology which people were not doing at the time. Additionally, I felt that changing the focus slightly to that of a systems-based approach and broadening the scope to all phases of testing would be most beneficial to pathologists.

We started small, initially in anatomic pathology, about seven years ago. It slowly grew to a department-wide initiative to include any pathology error, both AP and CP. We look at all phases of testing (i.e. pre-analytic, analytic and post-analytic). Even transcription errors, incorrect assignment of consultation cases and hand-off errors are looked at. We try to invite all pertinent stakeholders, even if from outside the department. It is a real public affirmation of patient safety. The opportunity for learning and collaboration is best accomplished through a completely transparent and collaborative process. We now are accredited via Harvard Medical School and offer risk management credit.

The conference has evolved into a rigorous format where we focus on the following themes for discussion.

- Evaluate adverse events or near misses thoroughly and honestly.

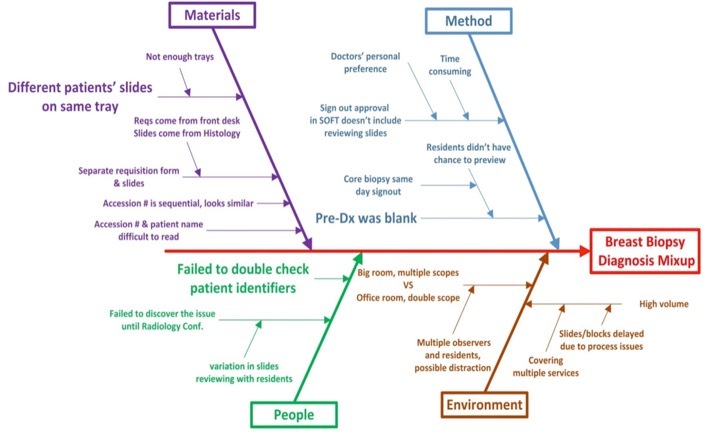

- Analyze root causes that may have contributed to the failures.

- Identify approaches to address the existing problems.

- Formulate a follow-up plan to affect changes in physician behaviors, systems, or processes.

- Promote open discussion and transparent culture for healthcare quality and patient safety.

The response from colleagues, staff, and hospital administration has been amazing. Initially, there was some sense of fear and perhaps shame about the concept of a public discussion of error(s). Feedback on follow-up surveys has been overwhelmingly positive. One major recurring theme is that participants are amazed at the complexity of healthcare processes. Recognizing this complexity, they leave the conference with an increased understanding of ways in which collaboration among departments can occur. I get a sense there is a feeling of relief among staff that these issues are finally addressed in a meaningful manner.

In the age of physician burnout, I feel this is one avenue in which participants can achieve some degree of satisfaction knowing their efforts directly impact patient safety and care. As a result, the culture has now shifted towards the mindset of "what can we innovate now to make the system better." That is a mission-based task that is very easy to bring people together.

One frustrating aspect is when the solutions seem daunting. This is best exemplified by healthcare information technology issues which are often the most difficult and expensive solutions to implement. However, from a strategic standpoint, this is valuable input for leadership.

Overall the value has been transformative for the department and hospital. The hospital healthcare quality administration utilizes our data for accreditation and regulatory reporting of patient safety events.

You speak a lot on the topic across the country. What are some of the common questions you get from audiences?

Dr. Heher:

These typically fall into two categories. The first is, "How did you do this?" For us, we established tangible goals and did it in a step wise manner over several years. Pathologists should start small and pick one local issue to work on and use the experience to tackle larger problems. You do not need to be heavily resourced to start small and build the quality and safety program practically over time.

The second set of questions I receive involve disruptive faculty and human resource type topics. In my experience, these HR issues are far outweighed by systems issues. HR issues around personnel attitude and/or competency must be handled in a professional and standard manner. M&M rounds are not the forum to air these issues

How do you handle faculty or other lab staff who are reluctant to discuss errors?

Dr. Heher:

I try to understand their concerns and objections, having a one-on-one discussion with the person. I have learned an incredible amount using this approach as frequently their worries are reasonable and can be valuable to the process. We have learned to integrate a lot of the feedback from staff who were initially resistant, and in doing so, made the system much better.

Can you speak about safety culture versus the concept of "psychological safety" and how those play into patient safety and organizational improvement?

Dr. Heher:

Amy Edmondson of Harvard Business School originally described this concept. The idea is that people within all levels of a hierarchy can feel comfortable coming forward with ideas. In a business setting, an example would be a junior executive who offers thoughts on strategy in a board meeting. The concept can also be extrapolated to the healthcare setting. Many times, the best ideas for process improvement come from those who are closest to those processes. Frontline employees know best about the granularity of the system, but they need to feel safe and empowered coming forward with ideas for improvement. This concept of "psychological safety" is fundamental to foster a successful culture of safety.

How can those without such a program take the first steps towards getting started?

Dr. Heher:

As I mentioned previously, one should start small, by identifying a problem and solving it. If there is more appetite for growth of a program, I would consider implementing Pathology M&M Conference, even within a single division at first before spreading it more widely. When we have generalizable solutions, we need to do a better job in promoting the use to our colleagues through increased publications. Colleagues do look to the literature for guidelines.

I believe that many of the pathology journals are behind in publishing editorials and healthcare delivery science on quality. We can do a better job of catching up with the House of Medicine on this topic.

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) and the National Patient Safety Foundation (NPSF) have incredible educational resources. Several helpful white papers are available for download and review. One particularly useful tool from the IHI is the RCA which details ways to improve root cause analyses.

The field of pathology needs a centralized resource where quality and safety materials are available for all pathologists to download. Dr. Raouf Nakhleh and I recently got a certified Patient Safety Course approved by the American Board of Pathology for CC, formerly MOC, credit.

Any last remarks for pathologists wanting to learn more?

Dr. Heher:

Despite recent advances, pathology is still underrepresented in the quality and safety movement. As more healthcare systems adopt the concept of "high-reliability organizations (HRO)" and implementing a culture of safety, pathologists need to step up and apply these principles to the laboratory.