- Home

- Member Resources

- Articles

- Dr. Georgios Papanicolaou: Father of Cytopathology and Inventor of the Pap Test

The specialty of pathology is taking on an increasingly multinational flavor due to the high number of international medical graduates matching into US pathology residency programs. As of 2019, IMGs accounted for nearly 31% of active pathologists in the United States, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges. Bolstering this trend is a long history of immigrant contributions to the practice of pathology. After all, an immigrant pioneered one of the greatest diagnostic advancements of the last century—a technique still in use today. Thus, for National Immigrant Heritage Month, we turn our lens to the life and work of Dr. Georgios Papanicolaou, inventor of the Pap test.

Born in Greece in 1883, Georgios Papanicolaou initially studied the humanities and music at the University of Athens. Encouraged by his father, a physician, he stayed on to pursue a degree in medicine, later obtaining an additional degree in zoology from the University of Munich. It was during his return to Greece that he met his future wife, Andromache Mavrogeni; they married shortly thereafter. Though he worked as a physician for a short time in his home country, Dr. Papanicolaou’s true interest was in biological research. At that time, America boasted a more robust medical research field, prompting the couple to immigrate to the United States in 1913 in search of opportunities.

Dr. Papanicolaou would later recall that they came with only around $250 between them—the minimum amount then required to enter the country—and neither knowing any English. With no pre-arranged employment, he worked odd jobs to make a living. Andromache, who went by Mary in her new country, found work as a seamstress. Eventually, Dr. Papanicolaou gained a foothold into his chosen field via a part-time research position in New York Hospital’s pathology department. Soon after, he secured a full-time job as a laboratory assistant in the anatomy department at Cornell University Medical College. Mary joined her husband as his technician, though she was unpaid.

His position at Cornell afforded him the venue and resources to pursue his research. Using guinea pigs as his initial subjects, Dr. Papanicolaou observed that histologic changes in the reproductive tract during the estrus cycle were also detectable in vaginal secretions when viewed under a microscope. He then sought to replicate these findings in humans. But without a physician’s license to practice in the US, obtaining access to patient samples was difficult. His wife would prove herself indispensable to the next phase of his research.

Beginning in 1920, Mary served as his sole test subject and provided daily samples for study under the microscope, helping to prepare and analyze her own swabs. Over time, she was able to recruit female friends to give additional samples. These contributions allowed her husband to replicate his findings in humans.

As his studies gained momentum, Dr. Papanicolaou gained access to samples from patients in Cornell’s gynecology clinic. In conducting tests on the larger sample group, he realized he could distinguish malignant cells from non-malignant cells when examining the slides under a microscope. This meant that the collection of cells from the reproductive tract could be used in the diagnosis of related diseases, including cervical cancer—a major medical breakthrough.

In the early 1900s, cervical cancer was the leading cause of cancer death among US women, with an estimated 40,000 women succumbing to the disease per year. The cancer typically went undiagnosed until it had reached a very advanced stage. Dr. Papanicolaou and his team had discovered a low-cost, non-invasive means for early detection. He presented his groundbreaking findings at a conference in 1928, but the medical community was initially resistant, partially due to the novelty of using cells for diagnosis rather than taking whole tissue samples. Additionally, Dr. Papanicolaou’s limited English in his early published works worked against him.

Despite this setback, he persevered, publishing twice more on his findings, first in 1941 and again in 1943. The latter work provided guidance on how to correctly collect cell specimens and interpret the findings. Finally, the medical community took notice. By the end of the decade, the Papanicolaou test—or Pap test, as it came to be known—was in widespread use, and cervical cancer rates had dropped by half. The rates continued to decline in the following decades, finally leveling off in the early 2000s at around 12,000 new cases per year, resulting in approximately 4,000 deaths—a decrease of nearly 90% from pre-Pap test levels, depending on the sources.

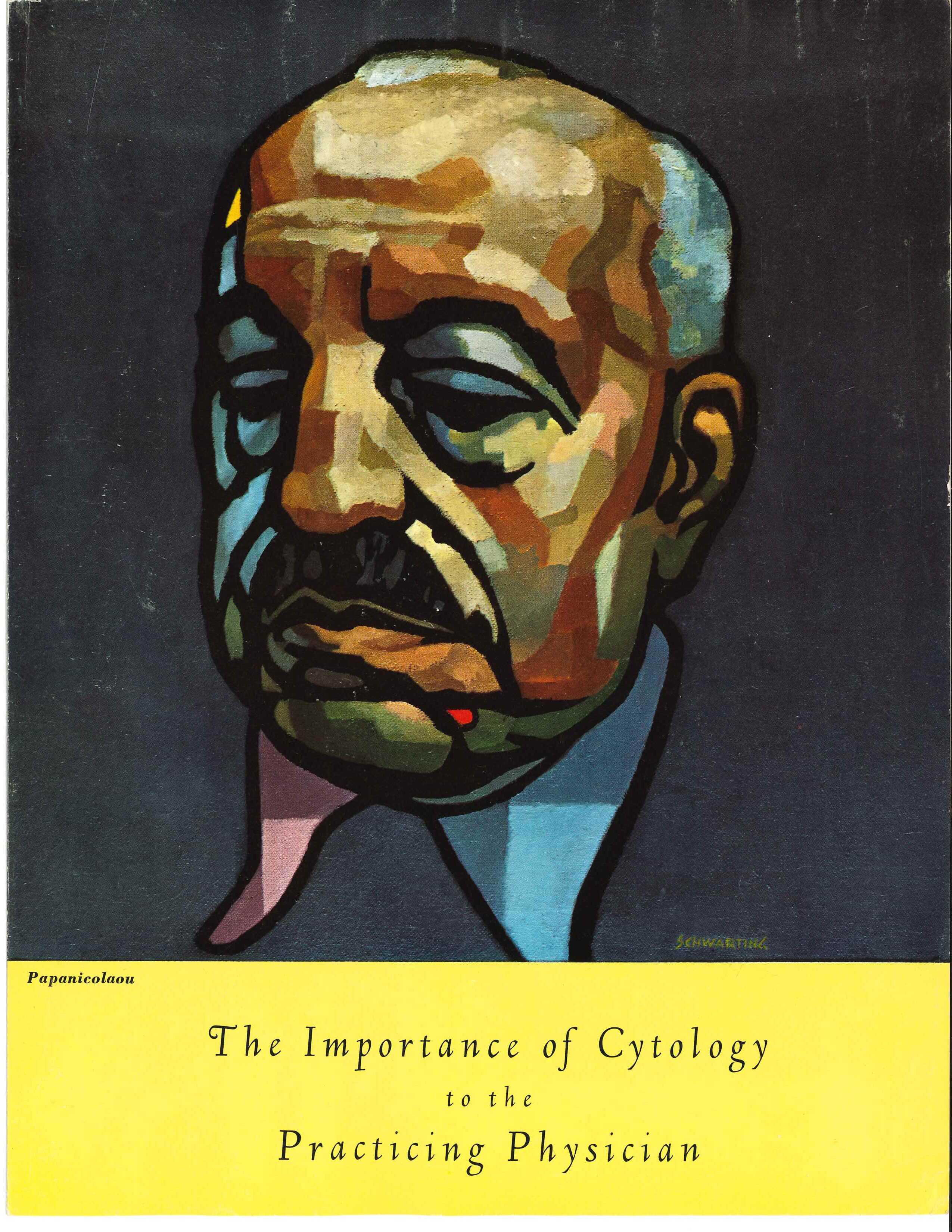

Once the leading malignancy among women, cervical cancer is now seen as a highly treatable and preventable disease, largely thanks to Dr. Papanicolaou’s pioneering methods. His work was also fundamental to establishing cytology as a viable discipline and means of diagnosis. Throughout the 1950s, the CAP supported the development of cytotechnology standards and training criteria for certification of cytotechnologists. In 1956, the organization recognized Dr. Papanicolaou as an honorary fellow, and in 1958, the CAP sent out an educational brochure detailing cytology guidelines to all US physicians. Fittingly, Dr. Papanicolaou was featured on the brochure’s cover.

For National Immigrant Heritage Month, we celebrate the achievements of Dr. Georgios and Mary Papanicolaou, while also making note of the barriers immigrants face when integrating into our society and the costs therein. Cervical cancer unnecessarily claimed the lives of an untold number of women in the years it took for the Pap test to gain acceptance. However, many more lives have been spared in the years since its adoption. When all are allowed to contribute and given adequate support, pathology—and the practice of medicine at large—is made stronger.