- Home

- Member Resources

- Articles

- Utilizing Cell-Free DNA Technologies for Clinically Significant Biomarkers in Solid Organ Transplantation

Background

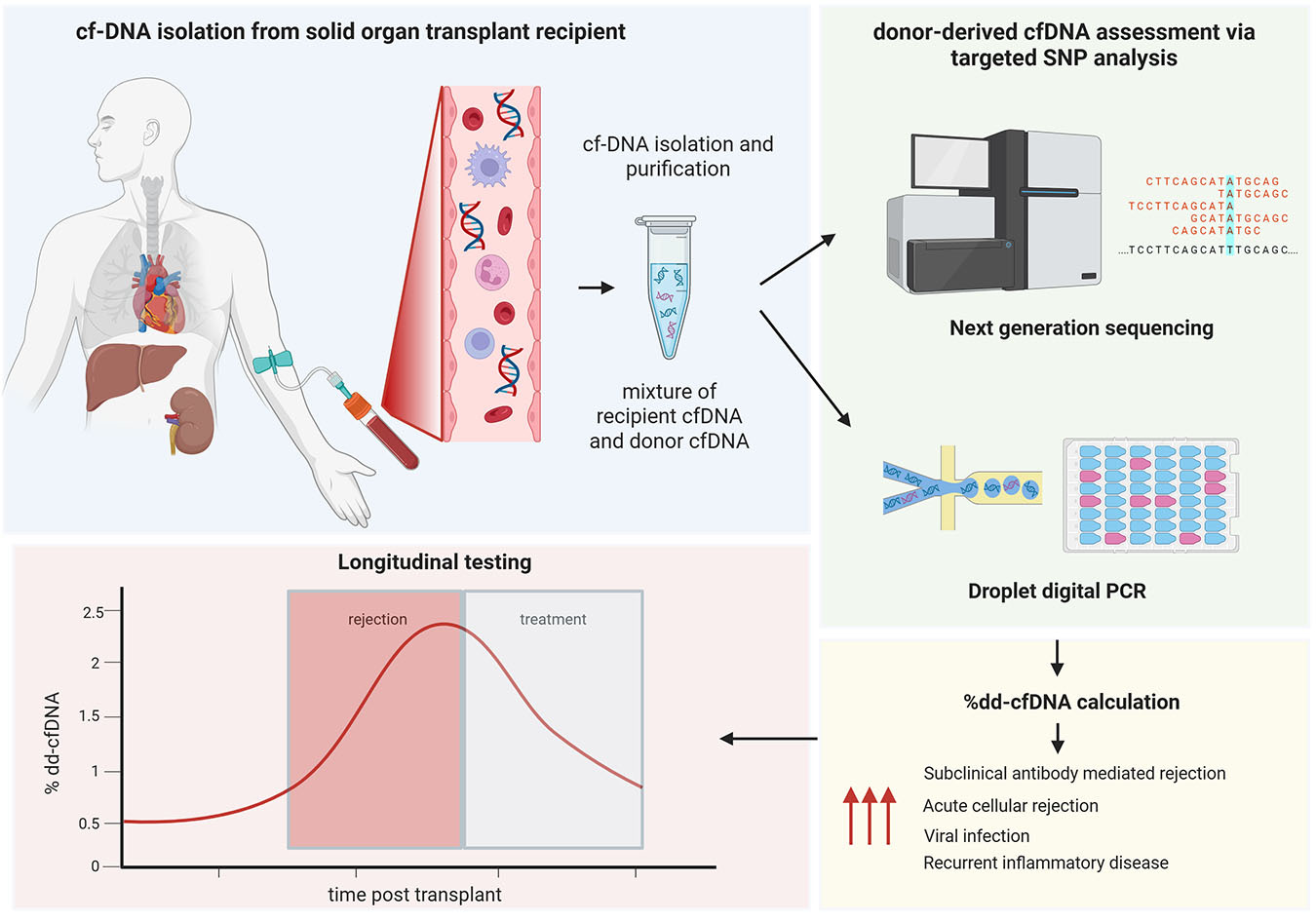

Solid organ transplantation is a critical treatment for end-stage disease, but post-transplant complications, such as acute rejection, remain a significant challenge. Traditional monitoring methods, including biochemical tests and biopsies, have limitations in sensitivity and specificity or are invasive with risks to the patient. Recently, donor-derived cell-free DNA (dd-cfDNA) has emerged as a clinically useful noninvasive biomarker for monitoring solid organ transplant health. Additionally, measurement of mitochondrial cfDNA (mt-cfDNA) and methylation patterns of cfDNA are emerging biomarkers of interest in the transplant setting. This article will introduce the principles of dd-cfDNA testing in solid organ transplantation, methods of detection, clinical applications, and the potential of cfDNA to improve transplant outcomes (Figure 1).

cfDNA refers to extracellular double-stranded fragments of DNA present in biological fluids, including plasma (learn more). The majority of cfDNA originates from hematopoietic cells during cellular apoptosis or necrosis and are cleared from plasma by the liver, spleen, and kidneys. cfDNA has a relatively short half-life, supporting its use as a real-time marker of cellular injury or turnover.1,2

In transplantation, the fraction of the cfDNA derived from the graft donor cells of the transplanted organ (donor-derived cfDNA or dd-cfDNA) is typically very low. Under normal conditions, dd-cfDNA levels decrease after transplantation as the organ stabilizes3; however, elevated levels indicate cellular injury within the transplanted organ due to acute rejection, infection, or ischemia.4–6 During acute rejection, immune-mediated injury causes apoptosis and necrosis of graft cells, releasing donor-derived DNA into circulation. Similarly, ischemic or infectious injuries elevate dd-cfDNA levels. While distinguishing causes of allograft injury using dd-cfDNA is not yet reliable, low dd-cfDNA levels represent a useful negative predictor of acute rejection. Additional advantages of utilizing dd-cfDNA as a biomarker include noninvasiveness, as cfDNA testing requires only a blood sample; the potential to detect graft injury earlier than other methods or to enable the detection of subclinical grade injury; and the potential of real-time monitoring, as cfDNA reflects active cellular processes in real time, offering dynamic assessments of graft health when compared to static biopsy results.

Initially, detection of dd-cfDNA in transplant recipient plasma was performed by identifying genetic sequences unique to the Y-chromosome in female patients who had received liver or kidneys from male donors, amplifying these sequences via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and visualizing them using gel electrophoresis.7 This demonstrated the concept of donor-specific cfDNA. The focus then shifted to identifying more genetic targets that could be used to differentiate donor and recipient DNA.

Molecular Methods of Measurement

While detection of dd-cfDNA can be performed with short tandem repeat analysis as in typical engraftment studies, the possibility of identity testing using a vast multitude of single nucleotide polymorphisms has led to commercially available and clinically validated assays utilizing either next-generation sequencing (NGS) or droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) methods (Table 1). These tests are available as a clinical test service for physicians to order or as a kit for laboratories to utilize.

Table 1. ddPCR and NGS comparisons for dd-cfDNA measurements

| Method | Difficulty of development (wet-bench, instrumentation, and bioinformatics) | Sensitivity | Turnaround time | Cost | Standardization / multiplexing flexibility | Commercial assays |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ddPCR | Low | Clinical: Not yet established, likely comparable to NGS Analytical: Very high (LOD 0.002% dd-cfDNA) | Rapid (<48 hours) | Low | Less opportunities | GraftAssure (ddPCR) |

| NGS | High | Clinical: Not yet established, likely comparable to ddPCR Analytical: High (LOD 0.12-0.15% dd-cfDNA) | 2-3 days | High | More opportunities | AlloSure (NGS) Prospera (NGS) |

NGS methodology can be used to perform targeted sequencing of multiple single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) to detect genetic sequences likely to differ between donor-recipient pairs, meaning a set of preselected SNPs with high minor allele frequencies across diverse populations. NGS assays can be complex and expensive, and they can take several days to process, making them potentially futile as a real-time biomarker; however, NGS methodologies constantly improve, and turnaround times of two to three days can be achieved. ddPCR methods similarly utilize preselected SNPs to differentiate donor and recipient DNA; however, they allow for more precise quantification with faster turnaround time (less than 48 hours). Because of the high accuracy of ddPCR, this method does not require analysis of as many SNPs as NGS methodologies.

In general, ddPCR methods achieve higher analytical sensitivity at lower cost. For example, the limit of detection (LOD) in ddPRC methods has been reported as low as 0.002% dd-cfDNA with limit of quantification of 0.038%,8 compared to reported LODs of 0.12% to 0.15% dd-cfDNA for NGS methods9; however, ddPCR methods have narrower multiplexing and less standardization than commercial NGS-based platforms, and clinical specificity and sensitivity for rejection are broadly comparable between the two methods when optimized cutoffs are used. ddPCR and NGS methods do not require prior donor genotyping, as leveraging a sufficiently large and diverse SNP panel allows discovery of enough informative markers for accurate calculation of percent dd-cfDNA.10 At this time, there is no standardization for targeted SNPs in commercially available assays, and the targets vary, as the number of SNPs range from approximately 200 to over 13,000. The result may be reported as percent dd-cfDNA and/or an absolute copies/mL, depending on the specific assay.11,12 Threshold for positivity can be set at a specific percentage of dd-cfDNA, and some assays use a dynamic threshold based on a baseline measurement.

cfDNA tests require special collection considerations, as cell lysis can contaminate the cfDNA content. Typical EDTA tubes can theoretically be used, but the plasma needs to be isolated and stored at -80 °C within one hour of collection, which is not always practical. For this reason, special preservative tubes that stabilize the cfDNA in blood (Streck tubes) are typically used for cfDNA collection.

Clinical Applications of cfDNA

Kidney Transplant Surveillance

In kidney transplant recipients, dd-cfDNA is a significantly better discriminator of rejection or allograft injury than serum creatinine.13,14 dd-cfDNA is considered a leading indicator of de novo donor specific antibody (DSA) development, compared to creatinine, which is a lagging indicator.14 Low dd-cfDNA levels provide strong evidence against rejection and allow the ability to forego unnecessary biopsies, while elevated or rising levels signal a markedly elevated risk of rejection. Recently, dd-cfDNA has emerged clinically as a valuable adjunct in diagnosing kidney transplantation rejection and in monitoring the response to treatment. The American Society of Transplant Surgeons (ASTS) released a statement on the use of dd-cfDNA in October 2024. In kidney transplant recipients, ASTS recommends use of dd-cfDNA levels in those with acute allograft dysfunction to exclude rejection, particularly antibody-mediated rejection (AMR), and suggests serial dd-cfDNA levels in those with stable allograft function to exclude subclinical AMR (Table 2). Because clinical adoption of this molecular technique is fairly new, the best testing frequency for surveillance is an area that is still evolving.

Table 2. Summary of dd-cfNDA clinical utility and validated assays by organ type

| Organ | Professional guideline recommendations [ASTS Oct. 2024 position statement] | Validated assays | Promising research purposes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kidney |

|

|

|

| Heart |

|

|

|

| Liver |

|

|

|

| Other (lung) |

|

|

|

Heart Transplant Surveillance

Recent studies show that dd-cfDNA rules out clinically significant acute rejection in heart transplant recipients and decreases need for invasive endomyocardial biopsies.15–17 In addition to success in external commercial laboratories, this testing has shown feasibility of use in local laboratories using commercially available kits as well.18 In heart transplantation, ASTS suggests that dd-cfDNA can be used to rule out subclinical rejection and to use it in conjunction with peripheral blood gene expression profiling to rule out acute rejection in stable, low-risk, adult heart transplant patients that are over 55 days status post-transplant. Like kidney transplantation, ideal surveillance testing schedules are still being investigated.

Other Uses in Solid Organ Transplantation

There are other uses of dd-cfDNA in organ transplantation that are not yet clinically validated or recommended by ASTS but are being explored in the research setting. For example, uses of dd-cfDNA are also being explored in liver and lung solid organ transplantation, which show promise but have issues related to increased biologic complexity.

In lung transplantation, elevated levels of dd-cfDNA have been correlated with graft rejection and infection.19,20 Pilot studies related to chronic lung allograft dysfunction show that dd-cfDNA can detect ongoing allograft injury but lacks specificity, as there are many nonrejection sources of tissue injury that elevate dd-cfDNA.21

In liver transplantation, several studies have shown superior sensitivity and specificity of dd-cfDNA for detecting rejection compared to traditional biomarkers.22,23 Again, the distinction of the cause of allograft injury was not reliable, but there seems to be added value in the rapid increase of dd-cfDNA prior to standard liver function tests and clinical symptoms24; however, some studies seem to contradict this, with dd-cfDNA showing poor positive and negative predictive value for assessment of subclinical graft injury.25 This may be because the liver is a large regenerative and metabolically active organ, and dd-cfDNA levels are naturally higher compared to other solid organ transplants, making setting a diagnostic threshold for injury or rejection difficult.26,27

Besides diagnosis of graft injury, dd-cfDNA has also been proposed as a way to investigate pre-transplantation machine perfused organ integrity (in addition to mt-cfDNA), adding another potential factor to support the decision of whether to use a graft prior to transplantation.28

As previously alluded to, differentiating causes of graft dysfunction is an area of active research. In the current state, quantitative analysis of dd-cfDNA alone is not specific in differentiating rejection from other allograft injuries22,29; however, there are newer methylation-based analyses being investigated to potentially differentiate types of graft injury based on methylation patterns of cfDNA.30

Additionally, recent studies have suggested added value of dd-cfDNA measurement for longitudinal monitoring of patients with an established diagnosis of AMR undergoing treatment.31

Conclusion

dd-cfDNA represents a paradigm shift in solid organ transplant monitoring by offering a noninvasive and sensitive marker of graft health at the molecular level. It enables early detection of complications such as acute rejection and provides insights into subclinical injury mechanisms while reducing reliance on invasive biopsies. Although challenges remain regarding cost, standardization, optimal threshold setting, and test specificity, ongoing research continues to refine this promising tool. As cfDNA-based assays become more accessible through clinical validation, they are poised to become integral components of personalized transplant care pathways. Currently, the role is in the high negative predictive value to prevent unnecessary biopsies and in early detection of allograft injury, and evidence-based guidelines suggest or recommend its use in heart and kidney transplant recipients. Several emerging areas of research in the utility of dd-cfDNA are exciting, including incorportation with other parameters (proteomics, methylation data) in a machine learning approach and longitudinal studies to improve long-term graft function.

References

- Diehl F, Schmidt K, Choti MA, et al. Circulating mutant DNA to assess tumor dynamics. Nat Med. 2008;14(9):985-990.

- Sherwood K, Weimer ET. Characteristics, properties, and potential applications of circulating cell-free dna in clinical diagnostics: a focus on transplantation. J Immunol Methods. 2018;463:27-38.

- Oellerich M, Shipkova M, Asendorf T, et al. Absolute quantification of donor-derived cell-free DNA as a marker of rejection and graft injury in kidney transplantation: Results from a prospective observational study. Am J Transplant. 2019;19(11):3087-3099.

- Fernández-Galán E, Badenas C, Fondevila C, et al. Monitoring of Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA by Short Tandem Repeats: Concentration of Total Cell-Free DNA and Fragment Size for Acute Rejection Risk Assessment in Liver Transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2022;28(2):257-268.

- Bloom RD, Bromberg JS, Poggio ED, et al. Cell-Free DNA and Active Rejection in Kidney Allografts. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(7):2221-2232.

- McClure T, Goh SK, Cox D, Muralidharan V, Dobrovic A, Testro AG. Donor-specific cell-free DNA as a biomarker in liver transplantation: A review. World J Transplant. 2020;10(11):307-319.

- Lo YM, Tein MS, Pang CC, Yeung CK, Tong KL, Hjelm NM. Presence of donor-specific DNA in plasma of kidney and liver-transplant recipients. Lancet. 1998;351(9112):1329-1330.

- Clausen FB, Jørgensen KMCL, Wardil LW, Nielsen LK, Krog GR. Droplet digital PCR-based testing for donor-derived cell-free DNA in transplanted patients as noninvasive marker of allograft health: Methodological aspects. PLoS One. 2023;18(2):e0282332.

- Melancon JK, Khalil A, Lerman MJ. Donor-Derived Cell Free DNA: Is It All the Same? Kidney360. 2020;1(10):1118-1123.

- Sharon E, Shi H, Kharbanda S, et al. Quantification of transplant-derived circulating cell-free DNA in absence of a donor genotype. PLoS Comput Biol. 2017;13(8):e1005629.

- Kim PJ, Olympios M, Sideris K, et al. A two-threshold algorithm using donor-derived cell-free DNA fraction and quantity to detect acute rejection after heart transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2025;25(9):1895-1905.

- Kim PJ, Olymbios M, Siu A, et al. A novel donor-derived cell-free DNA assay for the detection of acute rejection in heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2022;41(7):919-927.

- Bloom RD, Bromberg JS, Poggio ED, et al. Cell-Free DNA and Active Rejection in Kidney Allografts. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(7):2221-2232.

- Bu L, Gupta G, Pai A, et al. Clinical outcomes from the Assessing Donor-derived cell-free DNA Monitoring Insights of kidney Allografts with Longitudinal surveillance (ADMIRAL) study. Kidney Int. 2022;101(4):793-803.

- Teszak T, Barcziova T, Bödör C, et al. Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA Versus Left Ventricular Longitudinal Strain and Strain-Derived Myocardial Work Indices for Identification of Heart Transplant Injury. Biomedicines. 2025;13(4):841.

- Teszák T, Bödör C, Hegyi L, et al. Noninvasive rejection surveillance after solid organ transplantations: analysis of the donor-derived cell-free DNA. Orv Hetil. 2024;165(33):1275-1285.

- Kim PJ, Olymbios M, Siu A, et al. A novel donor-derived cell-free DNA assay for the detection of acute rejection in heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2022;41(7):919-927.

- Teszak T, Bödör C, Hegyi L, et al. Local laboratory-run donor-derived cell-free DNA assay for rejection surveillance in heart transplantation-first six months of clinical experience. Clin Transplant. 2023;37(9):e15078.

- Rosenheck JP, Ross DJ, Botros M, et al. Clinical Validation of a Plasma Donor-derived Cell-free DNA Assay to Detect Allograft Rejection and Injury in Lung Transplant. Transplant Direct. 2022;8(4):e1317.

- Arunachalam A, Anjum F, Rosenheck JP, et al. Donor-derived cell-free DNA is a valuable monitoring tool after single lung transplantation: Multicenter analysis. JHLT Open. 2024;6:100155.

- Beeckmans H, Pagliazzi A, Kerckhof P, et al. Donor-derived cell-free DNA in chronic lung allograft dysfunction phenotypes: a pilot study. Front Transplant. 2024;3:1513101.

- Levitsky J, Kandpal M, Guo K, Kleiboeker S, Sinha R, Abecassis M. Donor-derived cell-free DNA levels predict graft injury in liver transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2022;22(2):532-540.

- McClure T, Goh SK, Cox D, Muralidharan V, Dobrovic A, Testro AG. Donor-specific cell-free DNA as a biomarker in liver transplantation: A review. World J Transplant. 2020;10(11):307-319.

- Fernández-Galán E, Badenas C, Fondevila C, et al. Monitoring of Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA by Short Tandem Repeats: Concentration of Total Cell-Free DNA and Fragment Size for Acute Rejection Risk Assessment in Liver Transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2022;28(2):257-268.

- Baumann AK, Beck J, Kirchner T, et al. Elevated fractional donor-derived cell-free DNA during subclinical graft injury after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2022;28(12):1911-1919.

- Zhao D, Zhou T, Luo Y, et al. Preliminary clinical experience applying donor-derived cell-free DNA to discern rejection in pediatric liver transplant recipients. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):1138.

- Schütz E, Fischer A, Beck J, et al. Graft-derived cell-free DNA, a noninvasive early rejection and graft damage marker in liver transplantation: A prospective, observational, multicenter cohort study. PLoS Med. 2017;14(4):e1002286.

- Sorbini M, Carradori T, Patrono D, et al. Circulating cell-free DNA in liver transplantation: A pre- and post-transplant biomarker of graft dysfunction. Artif Organs. 2025;49(4):649-662.

- Akifova A, Budde K, Choi M, et al. Association of Blood Donor-derived Cell-free DNA Levels With Banff Scores and Histopathological Lesions in Kidney Allograft Biopsies: Results From an Observational Study. Transplant Direct. 2025;11(5):e1794.

- McNamara ME, Jain SS, Oza K, et al. Circulating cell-free DNA methylation patterns indicate cellular sources of allograft injury after liver transplant. Nat Commun. 2025;16(1):5310.

- Osmanodja B, Akifova A, Budde K, et al. Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA as a Companion Biomarker for AMR Treatment With Daratumumab: Case Series. Transpl Int. 2024;37:13213.

Julianne Szczepanski, MD, BSc, FCAP, is an Assistant Professor at the University of Michigan Department of Pathology. Dr. Szczepanski received her BS degree from Oakland University, followed by her MD from the University of Michigan. She completed her anatomic and clinical pathology residency training, gastrointestinal and hepatobiliary pathology fellowship training, and molecular genetic pathology fellowship training at the University of Michigan. She has authored numerous papers and abstracts related to gastrointestinal, hepatic, pancreatic, and molecular pathology. Her academic interests involve the intersection of gastrointestinal pathology and molecular pathology translational research.

Annette S. Kim, MD, PhD, FCAP, is the Henry Clay Bryant Professor and Division Head of Diagnostic Genetics and Genomics at the University of Michigan. Dr. Kim’s research program has focused on the study of hematolymphoid malignancies, including miRNAs in myelodysplastic syndromes, myeloid and lymphoid mutational patterns, and test utilization management. She has served as a member of Molecular Oncology Committee and is currently chair of the Personized Healthcare Committee for College of American Pathologists. She is also program chair of the Association for Molecular Pathology and past chair of the ASH Subcommittee on Precision Medicine. In 2019, Dr. Kim was awarded the CAP Public Service Award, and in 2025 she received the CAP Laboratory Improvement Programs Service Award.